The Memory Decoding Challenge: Annual Awards 2025

Progress towards "decoding a non-trivial memory from a static connectome"

If we could decode a specific memory from a preserved brain - not just generic reflexes, but something unique to that animal’s experiences - it would provide powerful evidence that the information defining who an individual is can survive a preservation process. That's the premise behind the Memory Decoding Challenge: a $100,000 prize for the first team to demonstrate that a “non-trivial” memory can be read out from a static map of synaptic connectivity. This prize is run by the Aspirational Neuroscience community, which also gives out smaller annual milestone awards and hosts an ongoing journal club.

Last November, the Aspirational Neuroscience community held its third annual meetup at the Society for Neuroscience conference in San Diego to take stock of where we are. The following is a lightly edited transcript of the opening remarks provided by Kenneth Hayworth. While no group has won the main prize yet, based on this kind of progress, the expert panel discussion that followed the award ceremony think it will likely happen within the next five years.

Introduction

All right, well, thank you all for coming. Thank you for joining us for our third annual long-term memory encoding and connectome decoding meetup—we’re working on the name.

In a moment, I’ve got to announce the winners of this year’s Aspirational Neuroscience Awards, and then we can move on to the main event: the panel discussion. We have some really fantastic neuroscientists that are going to discuss what would it take to decode a non-trivial memory from a connectome? I think it’s going to be super interesting.

But before we go there, I want to give a kind of overview of what we’re trying to do.

A little over 15 years ago, a small set of neuroscientists were arguing that electron microscopy should be automated in order to allow for the dense mapping of neural circuits. For example, this 2009 paper from Sebastian Seung said this in the abstract:

“Another method [this is before connectomics essentially, or the most recent round of connectomics] will be to find a “connectome,” a dense map of all connections in a single specimen, and infer functional properties of neurons through computational analysis. For the latter method, the most exciting prospect would be to decode the memories that are hypothesized to be stored in connectomes.”

So right from the beginning of this EM connectomics era was the idea that an ultimate test of connectomics would be whether you can really decode the algorithm—whether you can decode memory and learned function from the connectome.

In the intervening years—let’s say 15 years—there has been a technological revolution. Hopefully people have caught the connectomics talks earlier today. There’s been a revolution in volume electron microscopy, such that we now do have access to increasingly large and accurate connectomes across a wide range of model organisms.

For example:

We recently got a Drosophila central nervous system—thankfully I got a small part in that project.

Other labs like the Allen Institute and their collaborators have produced this wonderful MICrONS connectome spanning several visual areas, complete with calcium imaging of those neurons.

Additional labs have mapped connectomes from other cortical areas and have gone on to map the hippocampus.

The whole zebrafish connectome is going to come online soon, again with calcium imaging.

The songbird, which is long used as a model organism for studying basal ganglia, is also having its connectome mapped.

In fact, these electron microscopy volumes are likely to be eclipsed in the next few years in terms of volume by light microscopy techniques like LICONN that use expansion microscopy and protein pan-protein staining that have been shown to be able to also produce connectomes.

And in parallel, there’s been a revolution in the genetic tools that can tag and manipulate engram cells that activate when a memory is recalled. Tools like eGRASP that allow tagging of synapses on engram cells and even the manipulation of synapses through chromophore-assisted light inactivation (CALI) and others.

Our Goal

Given all these advances—these advances in connectomics and memory engram manipulation—we thought it was time to revisit the bold ambition that kicked off one of the connectomics revolutions in the first place: Can we decode a non-trivial memory from a static connectome?

I think it’s probably true that this has not occurred yet. It’s not a really clearly defined goal, and we can discuss that tonight. But I think it is an achievable goal.

The Aspirational Neuroscience Outreach Project exists to bring together researchers in connectomics and researchers in memory and engrams in order to design concrete experiments with the explicit goal of decoding memories from a static map of synaptic connectivity.

One of the important things to take home is that such an experiment would really put to the ultimate test the theories of memory. We want something that, for this particular system, for this particular type of memory, this decoding challenge would ultimately say whether that is a true theory or whether it is not.

The Memory Decoding Challenge Prize

To that end, we have thankfully got a generous donor that is very enthusiastic about neuroscience. We put forward a Memory Decoding Challenge Prize with the goal to help motivate such collaboration.

It’s a $100,000 prize for the first neuroscience research team who can demonstrate the decoding of a non-trivial memory or other learned function from a static connectome.

Now, defining exactly what would constitute a “non-trivial memory” is something the whole group could discuss in the panel tonight. In essence though, it should constitute a crystal-clear demonstration that a neuroscience model of how memories are encoded in the structure of neural circuits is actually correct.

I want to be clear that I don’t see this as some impossibly distant goal. I see many research teams at SfN presenting research that are actively pursuing projects that could constitute such a demonstration.

Concrete Examples

Here are some concrete examples, just to help people understand the scale that we’re talking about:

Decoding the learned song from the connectome of the songbird HVC-to-RA circuit

Decoding the rudiments of a spatial map in the hippocampal system would certainly constitute decoding a non-trivial memory

Decoding specific fear memories in the amygdala might constitute it

Decoding receptive field properties of primary visual cortical neurons or higher-order visual cortical neurons

And many others—hopefully we can discuss this in the panel.

Annual Awards

Because it’s likely to take many years for any team to reach that milestone of decoding a non-trivial memory, we’re giving four $25,000 Aspirational Neuroscience Awards, hopefully each year, for research that seems to be on the path toward that ultimate goal, or is contributing to our understanding of memory and the engram.

We also run a biweekly journal club with a large (but unfortunately not too active) email discussion group. I want to invite anybody that really wants to dig into the literature, because we need help—we need experts to keep on top of the latest research. And frankly, we’d also like people with deep expertise in the field to help with nominating the right types of papers and judging them.

This Year’s Nominations

Our website has a list of papers that have been nominated for Aspirational Neuroscience Awards. This is a collective thing—it’s not like papers were nominated this year and if they didn’t win, they can’t win the next year. This is a collection of papers that have all been nominated, so any of them can potentially win in future years.

They have been sorted roughly into different categories just to give you an idea of what we’re looking at:

Correlation among synapses with shared history

Dendritic integration and neural modeling

Fear memory in the amygdala

A whole bunch of hippocampus work, as you can imagine

Labeling and photo-erasure of synaptic ensembles

Molecular mechanisms of learning

Synaptic structure-function correlations (this is really the name of the game in how we figure out what the different learning rules are—this is what we should be on top of if we’re looking for what can be done from connectomes)

Visual receptive field encoding

2025 Award Winners

I could make arguments that each one of these is the ultimate paper. So if anybody is here who is not winning an award, please accept my apology. But there we are—we had to choose.

And here are the winners:

I want to say there are some absolutely earth-shattering, fantastic papers that didn’t win. This should not be—we had a lot of discussion about it, and it was along the lines of: “Yes, this is earth-shattering, but is it on the critical path?” or “Yes, this was earth-shattering, but it was a little too many years ago.” Everybody on this list was just fantastic.

Let me give a very brief overview of the ones that won.

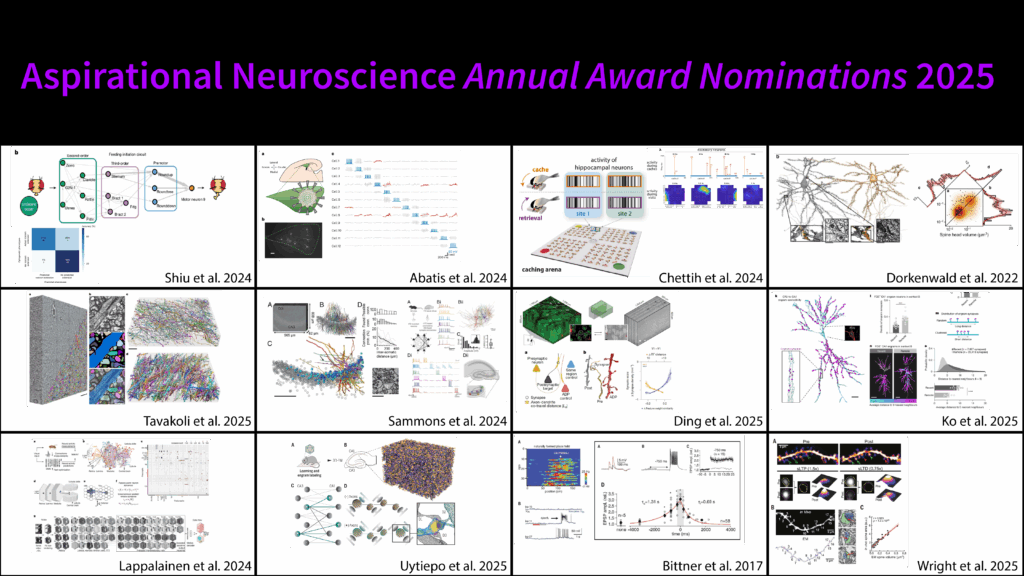

Award #1: Ko et al., 2025 - Systems consolidation reorganizes hippocampal engram circuitry.

This paper showed that shifts in episodic memory precision from specific to general—which is typically associated with cortical consolidation—may actually be partly explainable by synaptic reorganization in the hippocampus itself.

They used a combination of engram cell tagging and eGRASP synapse labeling to track the synaptic modifications underlying this gist memory formation.

One of the things that we found very impressive was tracking the change of a memory through tracking its synaptic changes.

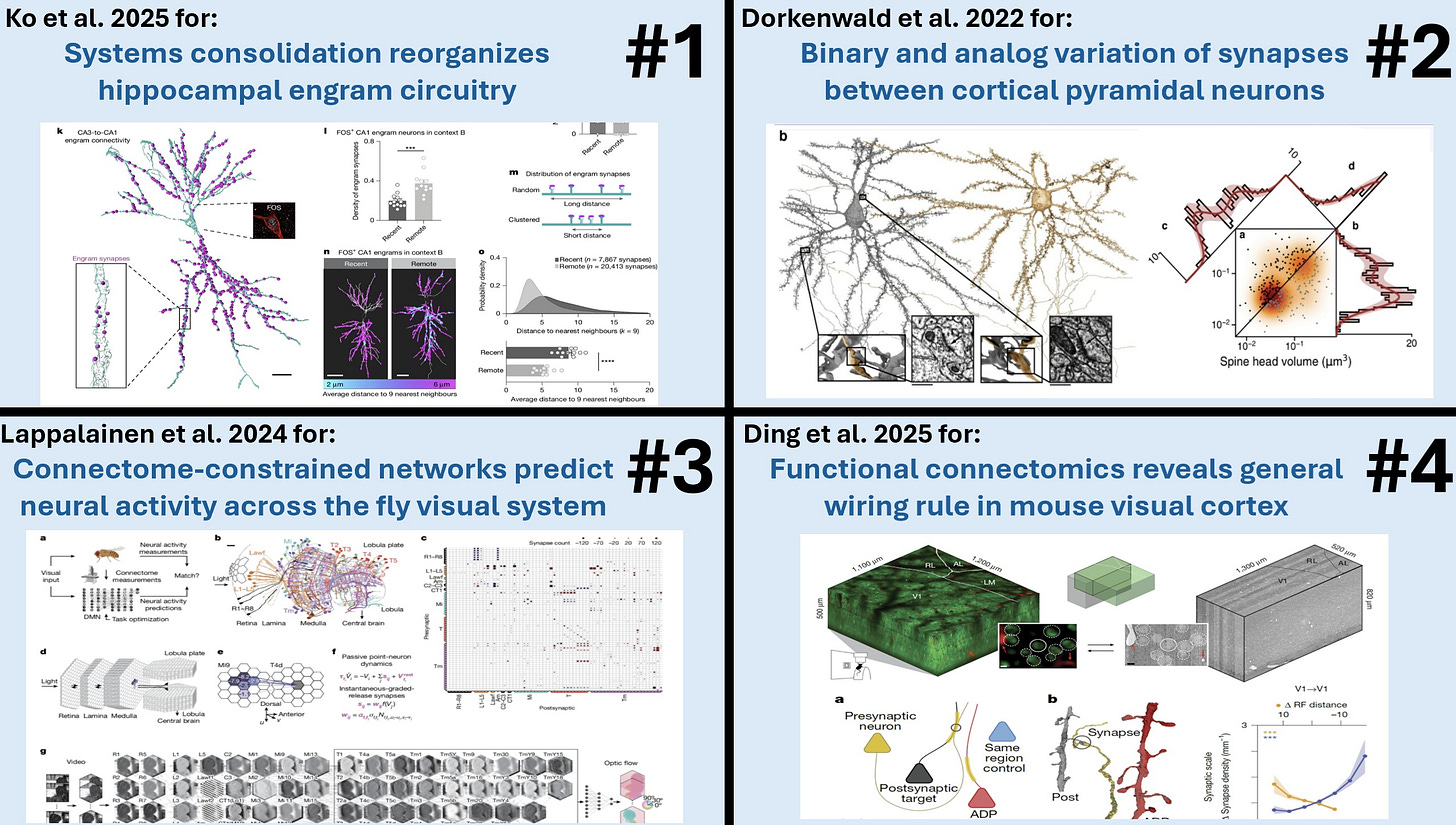

Award #2: Dorkenwald et al. 2022 - Binary and analog variation of synapses between cortical pyramidal neurons

This paper traced and proofread 1,960 synaptic connections among 334 pyramidal neurons in a TEM dataset covering layer 2/3 of mouse visual cortex. They quantified the size—and thus the functional strength—of each of these synapses.

Plotting a histogram of the synapses showed that instead of the expected log-normal distribution, a highly skewed distribution was seen that was better fit by a mixture of two log-normal distributions.

They then analyzed a subset containing 320 of these synapses from 160 matched pairs—two synapses that shared the same pre- and postsynaptic cells, such that they have the same learning history.

Plotting a histogram of the geometric means of each of these pairs showed an even clearer bimodal distribution, which the authors showed could be modeled by assuming that each pair had a binary value (either small or large) with an uncorrelated analog variable on top.

This is evidence that Hebbian-style learning operates with only two synaptic strengths: small versus large. This is cutting-edge stuff. It showed the real strength of having a large, accurately traced connectome.

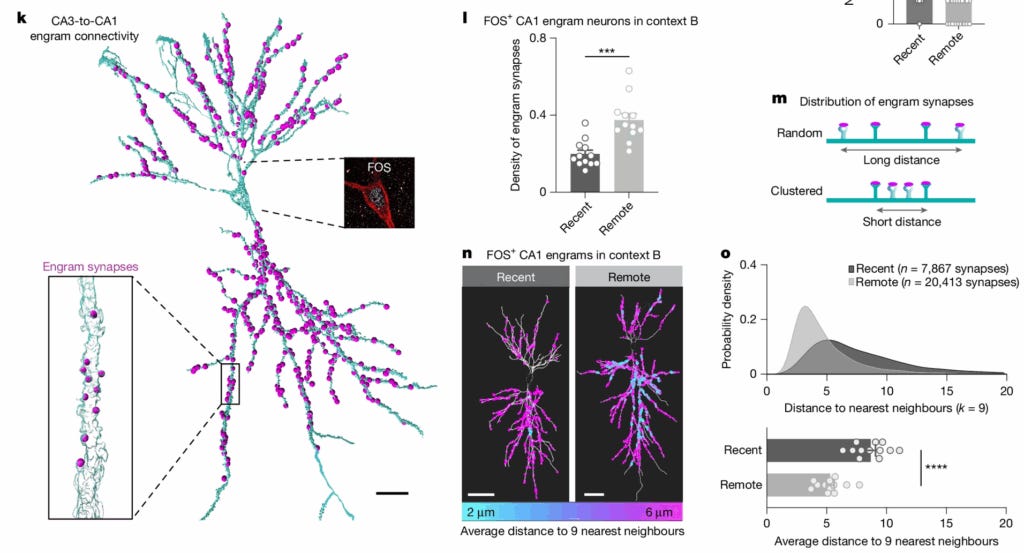

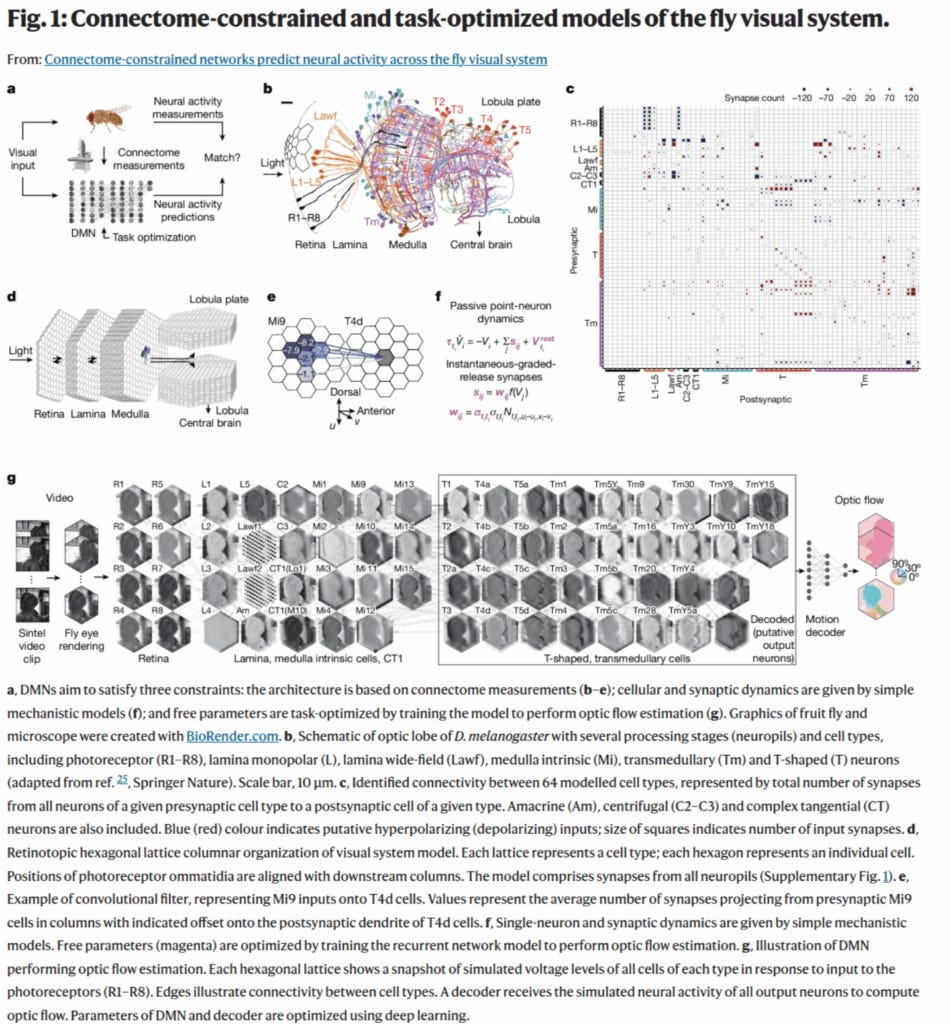

Award #3: Lappalainen et al. 2024 - Connectome-constrained networks predict neural activity across the fly visual system

This paper showed a novel way to predict function from a static map of synaptic connectivity, even when many dynamic parameters of the neurons and synapses are not known.

They generated a differentiable model of the fly visual system based on full EM connectivity, and this allowed the unknown dynamic parameters to be tuned by gradient descent with the goal of matching known motion selectivity of a subset of the neurons.

We thought this novel method showed how the considerable constraints of a connectome could be leveraged even if not all the dynamics are known.

I’ve heard talks around here about people thinking about trying this with the MICrONS dataset and other datasets—because you always have some dynamic factors in neurons that you don’t have when you just have the connectivity. So this shows a path forward.

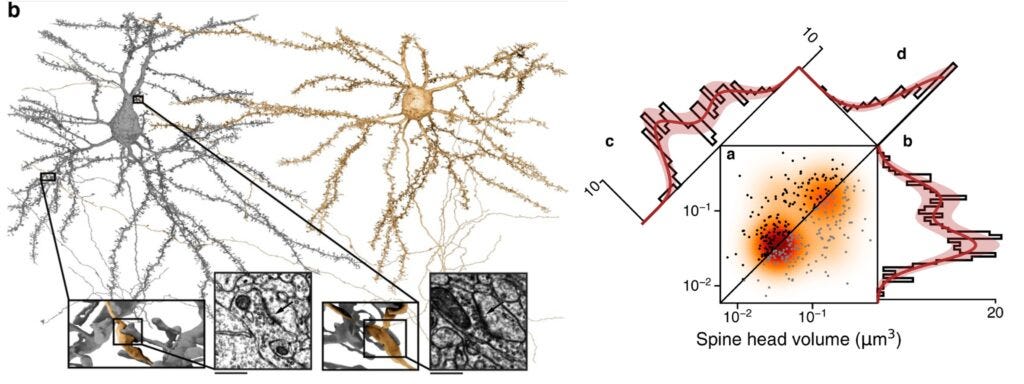

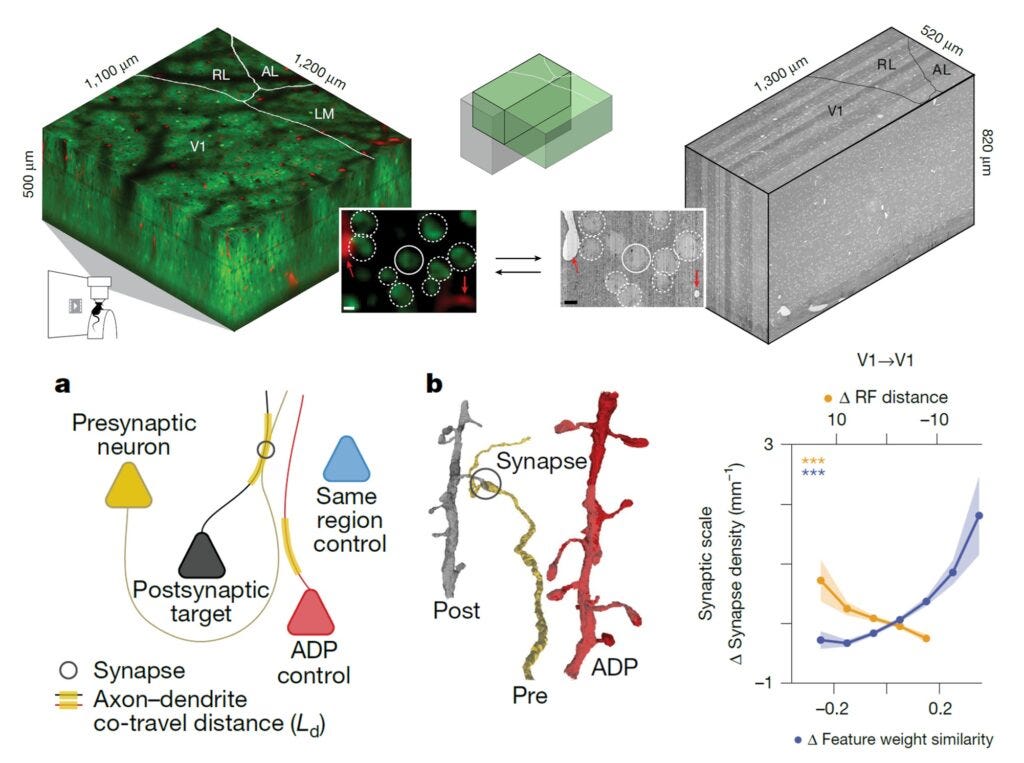

Award #4: Ding et al. 2025 - Functional connectomics reveals general wiring rule in mouse visual cortex

At some level, this paper had to win. The MICrONS project is perhaps the most ambitious connectomics project to date. It acquired a cubic millimeter volume of electron microscopy data spanning multiple primary and higher-order visual areas. Overlapping regions were calcium-imaged in the awake, behaving mouse while watching hours of specially designed video stimuli.

The paper analyzes a subset of neurons having both high-quality calcium recordings and proofread connectome tracing. This allowed the authors to ask questions like: Are neurons that respond to similar visual features more likely to be synaptically connected or not?

The authors employed some really novel analysis techniques (or at least, we did not see them in other papers at this level):

They quantified the distance each axon travels in close proximity to a dendrite, which allowed them to normalize the actual synaptic density between two cells. It’s not just asking whether two cells are connected—they’re first asking: Were they close enough to be connected? And then: Did they have a synaptic connection? A much stronger, tighter statistical question.

The authors also employed a digital twin to precisely quantify each cell’s receptive field location and its feature tuning.

Intriguingly, they showed that:

Cells with similar feature tuning have higher than expected synaptic interconnectivity (a result that other groups had seen before)

But cells with similar location tuning show lower than expected synaptic interconnectivity

I believe that has some serious implications for our understanding of how learning happens in the visual system and other sensory systems.

Conclusion

So in any case, these are the papers we awarded this year, and we should give them another round of applause.

[End of opening remarks and awards ceremony. Panel discussion follows, available here]

Here is a transcript of the podcast https://diyhpl.us/wiki/transcripts/connectome-memory-decoding-2025/