There’s always a first

...

Most people want to live longer, and in better health, than nature allows them to. This newsletter tracks efforts to give people more time, no matter how strange the means may be. But while I generally focus on modern technological developments, it’s the breakthroughs of our predecessors which give me hope that further progress is still possible.

1885

Everyone who contracts rabies dies within months…

Being mauled by an angry dog is terrifying enough, but if the animal is rabid, the bites are only the beginning of the horror. Once disease-carrying saliva is introduced into an open wound, rabies virus infiltrates nearby muscle cells and begins to replicate. Soon, it breaches the junctions between muscle cells and peripheral nerves, and at a rate of a few centimetres per day, begins climbing up nerve cells toward the brain1.

During this initial phase, the infected person experiences only subtle symptoms - perhaps a low-grade fever, or tingling near the bite wound. But once the virus reaches the brain, one of two nightmares commences: progressive paralysis or a descent into madness. For about half of patients, any attempt to drink triggers violent, involuntary throat spasms - leading to an overwhelming fear of water despite extreme thirst. Many also cycle between periods of manic rage and moments of terrifying lucidity, fully aware of their deteriorating condition.

The only mercy in this grim progression is its brevity. After about a week of torment – ending either in quiet respiratory failure, or a violent convulsive seizure – death inevitably arrives.

…until Joseph doesn’t.

On July 6, 1895, nine-year-old Joseph Meister becomes the first human test subject for a rabies vaccine. Two-and-a-half days earlier, he had been savagely attacked by his neighbour’s rabid dog, suffering wounds to his hands, legs and thighs. His desperate mother, having heard of Louis Pasteur’s experimental work, made an urgent and uncertain journey to Paris to seek help from the renowned scientist.

Surprisingly, she is in luck. Pasteur, having successfully developed a vaccine for anthrax a few years prior, has been quietly working on the same for rabies. By infecting rabbits with the disease, surgically extracting their spinal cords, and leaving them to dry, he has found a way to inactivate the virus. Dogs injected with a serum made from these dried nerves developed immunity, and so long as the injection was performed prior to symptom onset, every dog tested - without failure - became invulnerable to future infection.

Ten days later, and after twelve injections of progressively more potent vaccines, Joseph is still feeling fine (save for some soreness around the injection sites). Four months pass, and Pasteur receives a letter from Joseph’s mother reporting he remains in perfect health. Word of this miraculous success spreads rapidly. Within a year, Pasteur has treated hundreds of rabies patients from across Europe, and the first vaccination has occurred in America. In 1887, the Institut Pasteur opens in Paris as “a free clinic for rabies treatment, a research center for infectious diseases, and a teaching center.”

As of 2025, Rabies still claims about 60,000 lives annually, almost all in regions with limited healthcare access. Yet with 30 million vaccinations administered yearly, countless lives are saved from what was once a universally fatal disease.

1942

Everyone with severe blood poisoning dies within weeks…

Following an injury, surgery, or illness, bacteria sometimes invade the bloodstream. Multiplying rapidly, they release toxins that trigger a catastrophic inflammatory response. In unfortunate patients, high fever sets in as the body’s defences mount an insufficient counterattack. Organs fail one by one. Consciousness fades into delirium, a small blessing as the patient’s condition deteriorates. Despite sulfa drugs and blood transfusions, once the infection passes a certain point, the doctors’ efforts are futile.

… until Anne doesn’t.

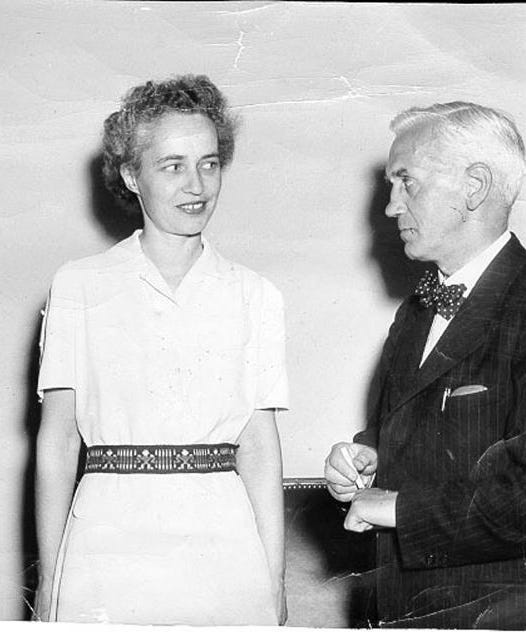

On March 14, 1942, thirty-three-year-old Anne Miller becomes one of the first people treated with antibiotics for an otherwise fatal blood infection.

Four weeks earlier, following a miscarriage, she had developed a raging streptococcal infection resistant to all available treatments. Her temperature had hovered dangerously high for a month, and the number of bacteria in her blood kept rising. Despite every medical intervention available, she lay delirious and dying at Yale Medical Center.

But to Anne’s extreme good fortune, one of the other patients in her ward had connections to Howard Florey’s pioneering penicillin research team. Through an urgent series of calls and telegrams spanning the eastern seaboard, her doctor secured 5.5 grams of the experimental drug – the first to be released for clinical trial in America. The precious substance, produced through the painstaking cultivation of a specific mold strain, arrived via air mail in a plain brown bag.

At 3:30 PM on Saturday, Anne received her first injection of the brownish solution. By the next morning, her temperature had returned to normal for the first time in four weeks. She began eating full meals, and gained strength with encouraging speed. Her blood, teeming with bacteria just days before, was soon completely sterile.

Anne left the hospital, and lived another 57 years. She raised three children, helped her husband start a school, and - as a nurse herself - witnessed the dawn of the antibiotic era that her own treatment helped inaugurate.

Three years after her infection, Alexander Fleming, who had first observed penicillin’s antibacterial properties in 1928, would meet Anne during a tour of the United States and declare her his “most important patient.”

Today, thanks to antibiotics, hundreds of thousands each year survive infections that once meant certain death.

1960

Almost everyone with end-stage kidney failure dies within weeks...

When someone’s kidneys fail completely, toxins accumulate in their bloodstream with merciless speed. Fluid builds up in their lungs, making each breath a struggle. Their skin may take on a sickly yellow-gray pallor as uremic frost – crystallized urea – forms on the surface. Nausea becomes constant, vomiting uncontrollable. Their mind grows foggy as toxins cross the blood-brain barrier. Seizures may follow. Their heart, struggling against rising potassium levels and fluid overload, eventually falters. Their merciful end comes through coma, then cardiac arrest – rarely more than a few weeks after diagnosis.

...until Clyde doesn't.

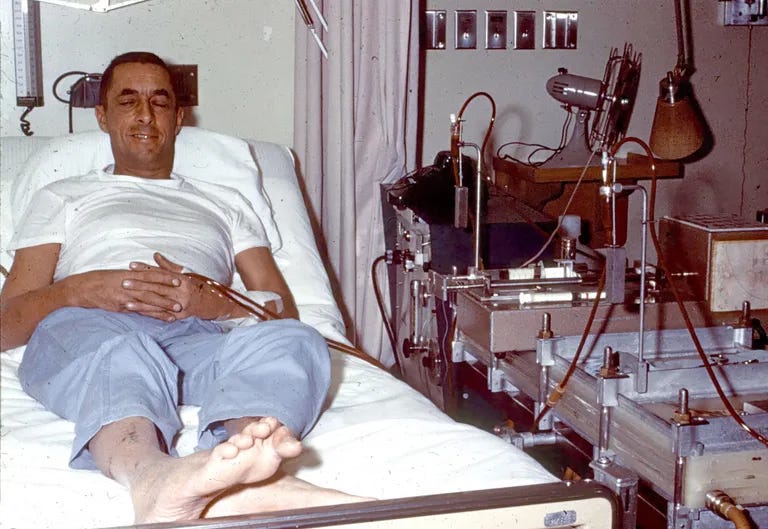

Clyde Shields arrives at the University of Washington Hospital in Seattle barely able to walk, vomiting constantly, his blood filled with toxic levels of waste products that his failed kidneys can no longer remove. Kidney transplantation is still in its infancy - most recipients don’t survive long - and there are no potential matches available for Clyde. As with all but the rarest patients with end-stage kidney failure, he will clearly die soon.

But Clyde’s physician is Dr. Belding Scribner, who has recently had a clever idea. Dialysis - extracting a patient’s blood and filtering it artificially through a machine - already exists, and is extremely useful for those with temporary kidney failure. However, it can only be performed a few times before veins collapse from repeated punctures, so its use is limited for those with chronic kidney issues. Yet Scribner envisions a permanent connection to the bloodstream – a shunt made of newly-invented Teflon tubing connecting an artery to a vein in a patient’s arm. The non-stick material, suggested by a colleague, prevents fatal blood clots that would form on any other surface.

Scribner implants the shunt, and after 76 hours of continuous dialysis, Shields walks out of the hospital and attends his child’s party – something unimaginable just days before. Twice weekly, for six to thirteen hours each session, he returns to the hospital to have his blood circulated through an artificial kidney that does what his own organs cannot. In 1966, he transitions to home dialysis, becoming one of the pioneers of a treatment that would eventually be performed in living rooms across the world.

Clyde lives for eleven more years before succumbing to a heart attack in 1971 – eleven years during which he watches his children grow, loves his wife, continues his work as a machinist, and serves as what Scribner called a “research partner” in refining the technology that saved him.

Today, over 2 million people worldwide receive regular dialysis; their lives continuing despite their kidneys failing. All owe their extra time to a machinist and a doctor who, in 1960, began humanity’s journey in replacing what were once ‘essential’ organs. As Shields’ son Tom would later reflect, “Those eleven extra years were so important to me. If Dad taught me one lesson, it’s don’t give up. Get back to work, and get 'er done.”

1990

Almost everyone with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) dies in early childhood...

When a child is born with an underdeveloped immune system, every common cold or routine infection becomes life-threatening. For those with adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency, a rare form of immune dysfunction, enzyme replacement therapy offers some temporary reprieve, but its effectiveness wanes. Even with isolation and constant medical intervention, pathogens still make it through. Parents watch helplessly as their child suffers through infection after infection, knowing that few will survive beyond toddlerhood.

...until Ashanthi doesn’t.

In 1990, four-year-old Ashanthi DeSilva has been diagnosed with ADA-SCID for two years. Despite weekly enzyme injections, her condition is deteriorating rapidly.

But just as it seems Ashanthi is running out of time, it turns out that she is not completely out of luck. Researchers have just developed an experimental treatment. Doctors propose drawing Ashanthi’s white blood cells and mixing them with a retrovirus carrying the functioning ADA gene. Unlike previous treatments, the virus will permanently update her cells with the instructions to produce the enzyme she has been missing since birth.

On September 14, 1990, Ashanthi receives her modified white blood cells back, and becomes the first genetically modified human.

Within months, her immune system begins functioning normally. The child who had been unable to fight off even minor infections starts to thrive. Ashanthi can now attend school with other children and live a relatively normal life – something previously unimaginable.

As of 2025, gene therapies treat conditions from inherited blindness to certain cancers. Ashanthi herself has grown up to become a patient advocate, a living testament to medical innovation.

1996

Everyone with advanced HIV/AIDS dies within months...

When HIV replicates unchecked and AIDS takes hold, the body loses its ability to fight off infections. Common illnesses become life-threatening as the immune system fails. Patients suffer through a predictable progression: recurring infections, dramatic weight loss, and increasing hospital stays. Doctors can treat each secondary infection as it appears, but cannot stop the underlying disease. Despite drugs like AZT, the end is inevitable - a series of increasingly severe illnesses until the body can fight no more.

...until Moisés doesn’t.

In 1986, Moisés Agosto-Rosario had been diagnosed with HIV, becoming the first person to publicly come out as gay and HIV-positive in Puerto Rico. Since then, he has become a prominent activist fighting for treatment access, particularly for communities of color. But with only ineffective treatments available, his health deteriorated precipitously over the next ten years.

At a 1996 reception in Vancouver held to say goodbye to their beloved advocate, colleagues speak movingly about Moisés, assuming these are his final days. But when Moisés himself takes the podium, he stuns everyone. Instead of the frail figure they expected, he speaks with vibrant energy and strength.

Moisés had recently participated in a clinical trial of “triple-combination therapy” - a cocktail of three drugs that attack HIV in different ways. The new treatment has triggered what would soon be called the “Lazarus effect” - a dramatic recovery from the edge of death.

As of 2025, millions worldwide receive similar treatments, living full lives with HIV. Moisés himself continues his advocacy work nearly three decades later, helping ensure that all communities benefit from these life-saving advances.

2012

Everyone with aggressive, relapsing leukemia dies within years...

When blood cancer proves resistant to treatment, traitorous cells multiply unchecked. Bone marrow fills with malignant cells, crowding out healthy blood production. Bruises appear easily. Fevers rage as infections take hold. Transfusions provide temporary relief, but cannot stop the disease. For people who relapse multiple times, the path narrows to palliative care – managing pain in their final months. Eventually, patients succumb to overwhelming infections, catastrophic bleeding, or organ failure as their bodies can no longer produce the healthy blood cells essential for survival.

...until Emily doesn’t.

In 2012, five-year-old Emily Whitehead is dying. Two years earlier, she had been diagnosed with leukemia. Despite aggressive treatment, her cancer returned twice. Her doctors recommended hospice care, giving her little chance of survival.

But with desperate determination, her parents found researchers who were developing a new approach. They had recently developed a therapy involving taking a patient’s own immune cells and reprogramming them to recognize and attack their cancer cells. Soon, Emily becomes one of the first people, and the first child, to be treated with CART therapy.

Emily’s cancer goes into remission. Rather than being admitted to a hospice, she instead starts school. She grows up, becomes a patient advocate, and lives life on her own terms.

Someday

Everyone dies…

To be alive is to be dying. In youth, growth and repair outpace damage, but this balance inevitably shifts with time. Energy that once seemed limitless begins to wane. Skin loses its elasticity and wrinkles. Hair thins and greys. Muscles diminish in strength. Joints stiffen and ache with accumulated wear. The heart pumps with decreasing vigor, making each physical exertion more challenging than the last. Risks of serious diseases – cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes – rise exponentially with each passing year. Hearing fades, vision blurs. Even taste becomes less acute, as if the world itself is becoming more distant.

Heedless of a person’s will-to-live, their body eventually reaches its limit, and they disintegrate. Their memories are erased, their dreams dissolve, and their way of experiencing the world is forever lost.

…until someone doesn't.

Nowadays, neuroscientists actually make use of this for tracing neural connections. First take the rabies virus and modify its genome so that it makes infected cells glow green. Next, inject it into an animal’s brain at a target location, wait a few days, and you can now image all the neurons that send output signals to the cells located at the injection site.

Good reminder of past major medical progress. 1942 stands out for me personally. A few years ago, for reasons unknown, I had an e. coli infection in my blood which got to my kidneys. I was extremely ill and hospitalized. In an earlier age, I would have died.

Beautiful, positive article! Please subscribe to my Substack too!