If you’re reading this, you’re one of the lucky ones.

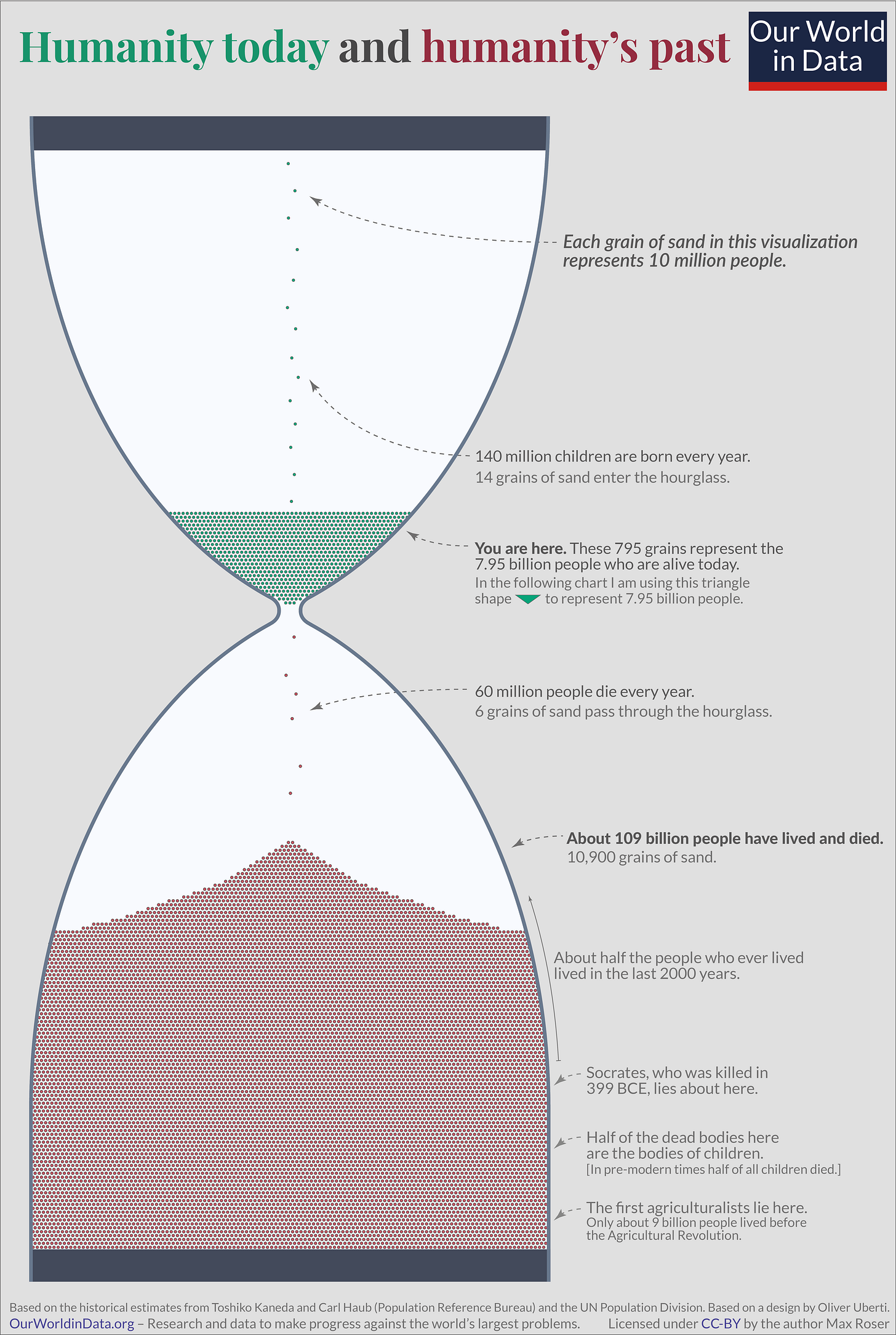

Not just because you're alive right now - though that’s remarkable enough. Of the roughly 120 billion humans who've ever lived, about 93% have already died.

But you're also lucky because, historically, you probably wouldn’t have survived long enough to read these words. Before modern medicine, sewage systems, and reliable food supplies, about half of all humans died before reaching fifteen. Infections we now easily treat with antibiotics killed countless babies. Diseases we now prevent with vaccines devastated communities. Famines that high-yield crops have made rare claimed millions of children. The past was, to put it bluntly, a terrible place to try to stay alive.

But don’t feel too grateful - you’re not that lucky.

If you're 40 and living in a developed country, your chance of dying this year is about 1-in-1000. That might sound reassuring. If that risk stayed constant, you'd live around 1,000 years on average before death caught up with you.

But it doesn't stay constant. Your chance of death rises exponentially as you age, doubling about every eight years. By 65, it's 1-in-100. By 80, it's 1-in-20. And by 90, it's 1-in-5.

Perhaps you're thinking: "Well, by the time I'm in my eighties, I'll probably be ready to go. I'll have spent time with family, achieved my ambitions, ticked off my bucket list. Sure, my children and grandchildren will miss me - I'd be a bit offended if they didn't - but after eighty-something years, I'll have had enough."

I hear this sentiment a lot, particularly among younger people. But having watched several of my loved ones pass away, I’m deeply sceptical that many elderly people actually feel this way. If medicine could have somehow offered my parents or grandparents a few more healthy years, I have no doubt they would have taken them.

There’s more reliable reasons for scepticism than just my anecdotal impressions though. When researchers have surveyed terminally ill patients, about 70% of them describe having a strong will-to-live, even as their deaths are imminently approaching.

This data isn’t supportive of the idea that most dying people are finished with life and ready to pass on. Rather, whether or not they’ve come to bravely accept their fates, or they’re terrified by the prospect of their impending ends, it suggests most of them would choose more time if they could somehow be given the chance.

This raises some uncomfortable questions. Why aren't we more outraged by our ever-increasing risk of death? How is it that we pour billions into treating cancer, heart disease, and dementia, yet barely acknowledge that aging itself is the root cause? Why does the National Institute of Health spend less than 1% of its budget studying the basic biology of aging? Why doesn't the FDA even classify aging as a disease? And how can a prestigious medical journal like The Lancet publish claims that "it is healthy to die" and "without death every birth would be a tragedy"?

I suspect it’s for the same reason that some nineteenth century surgeons claimed “Pain in surgical operations is in a majority of cases even desirable, and its prevention or annihilation is for the most part hazardous to the patient.”

Before anaesthesia was invented in the 1840s, surgery inevitably entailed unimaginable pain. For the surgeons who had to perform these traumatising but still potentially life-saving procedures, finding ways to desensitize themselves to their patients’ screams and groans would have been critical for their sanity. Some, perhaps to cope with the horror of their work, convinced themselves this suffering served a purpose. As one wrote in 1847, “I do not think men should be prevented from passing through what God intended them to endure.”

The parallel is striking. When we feel powerless to change something terrible, we often try to find meaning in the horror. We tell ourselves it must serve some greater purpose.

Although resistance to anaesthesia disturbingly persisted even for a short while after it was discovered, it didn’t last long. Once doctors saw it could work safely and effectively, their disdain transformed into embrace. Today, the idea that surgical pain might be “desirable” seems not just wrong but morally repugnant, and a surgeon claiming “it was a trivial matter [for patients] to suffer” would be at risk of being deregistered.

I hope we see the same attitude change repeat itself regarding the acceptability of death and the value of extending human lifespans. But for attitudes to shift, two things need to happen:

There need to be treatments that can actually extend human lives

People need to know the treatments exist, want to use them, and have access to them

Let’s start with the first.

Stopping ageing?

The ideal anti-ageing medicine would be some kind of pill which could stop ageing in its tracks. Imagine a treatment that could:

Stop any further ageing processes (e.g. DNA mutations, cellular senescence, or epigenetic dysregulation)

Reverse existing damage (e.g. plaque stuck to the walls of your arteries, tangled proteins accumulating in your brain cells, the shortening of the protective telomeres on chromosomes, or the wrinkled sagging of one’s skin)

Have a long-lasting duration (at least ten years?), after which point the pill could be taken again if one so chose

Be cheap and easy to distribute worldwide

Unfortunately, no such medicine exists. Worse, from my understanding of aging biology and the current research landscape, nothing like this is likely to emerge anytime soon.

It's not that it’s impossible in principle1. We know that some animals can live for centuries - just look at bowhead whales and Seychelles giant tortoises. Nor is it for a complete lack of trying. Companies like Calico and Altos Labs are investing billions in anti-aging research. Scientists are even testing whether the drug rapamycin can extend dogs’ lifespans. But so far, we have no proven way to slow aging, let alone reverse it.

Sure, there are some treatments for various ageing-related diseases such as cancer or heart disease. But in the absence of treating the underlying root-cause problem of ageing, this is just playing whack-a-mole. Even if cancer were cured entirely, it would only increase average life-expectancy by about three years. Why? Because, while three years is nothing to dismiss, some other ageing-related disease would shortly take it’s place.

I hope effective anti-aging treatments arrive soon. But for the 70 million people who will die this year, these future breakthroughs will come too late. Next year it might be your grandparent, your parent, your friend, or even you.

This is unacceptable. We need some way to stop people from dying, and we need it yesterday. But if we can’t yet halt ageing, what else could we possibly do?

Stopping time?

If we can't stop time's march forward, maybe instead we could step outside of it entirely?

Science fiction writers have long imagined placing people in a state of stasis - unconscious, unaging, and unchanging - until future medicine could safely revive them. You've probably seen versions of this in movies: Ripley in Alien, Captain America in Marvel films, or Fry in Futurama. Variously referred to as ‘suspended animation’, ‘cryosleep’, ‘cryostasis’, ‘cryonics’, ‘biostasis’, or just ‘preservation’, the hope is that some technology can be developed that can reversibly pause people’s lives for an indefinite period of time.

But it’s not just science-fiction writers - serious scientists have wondered about it too. As far back as 1773, Benjamin Franklin wrote:

I wish it were possible […] to invent a method of embalming […] persons, in such a manner that they might be recalled to life at any period, however distant; [I have] an ardent desire to see and observe the state of America a hundred years hence […] to be recalled to life by the solar warmth of my dear country!

Still, it took a couple of centuries before any significant efforts were put into actually attempting to preserve people.

In 1967, nearly two centuries after Franklin's wishful thinking, someone finally tried it. James Bedford, a psychology professor dying of kidney cancer, had his body cooled and submerged in liquid nitrogen immediately after his legal death2. His hope? That the cold would prevent decay until future medicine could cure his cancer and repair any freezing damage.

Preservation techniques have evolved considerably since then. The early methods struggled with a major problem: ice crystals. When water freezes inside tissues, it forms sharp crystals that puncture cells and dehydrate tissues - not exactly ideal for keeping a brain intact.

In the 1980s, scientists found a partial solution by improving the antifreeze chemicals (cryoprotectants) used before cooling. This prevented ice formation, but created new problems. The process caused severe dehydration, shrinking preserved brains by up to 50%. Organizations still using these methods haven't shown evidence that the crucial brain structures storing memories and personality survive this dramatic shrinkage.

In 2010, hoping to spur development of better methods, the Brain Preservation Foundation offered a $100,000 prize. The challenge? Develop a preservation technique that demonstrably keeps the microscopic structures of the brain intact.

Eight years later, two researchers claimed the prize with a new method called ‘aldehyde-stabilized cryopreservation.’ Their innovation was simple: before adding cryoprotectants and cooling, they introduced preservative chemicals (fixatives) that bound molecules in place, immediately halting decay. Subsequently cooling could prevent anything that the fixation might have missed. By using fixatives to stop decay quickly, and by also preventing the severe shrinkage of earlier methods, the method produced preservation quality that could hold up under the scrutiny of powerful microscopes. The judges' conclusion was striking:

…researchers have demonstrated for the first-time ever a way to preserve a brain’s connectome (the 150 trillion synaptic connections presumed to encode all of a person’s knowledge) for centuries-long storage in a large mammal. This laboratory demonstration clears the way to develop Aldehyde-Stabilized Cryopreservation into a ‘last resort’ medical option, one that would prevent the destruction of the patient’s unique connectome, offering at least some hope for future revival…

In other words: we might finally have a way to preserve people well enough to give them a verifiable chance at future revival.

Is this legit?

Throughout history, scientists have made bold claims about world-changing discoveries. Sometimes, like Francis Crick announcing “we have discovered the secret of life!” after finding DNA's structure, they're right. Other times, like Fleischmann’s and Pons’ claims of cold fusion, they're spectacularly wrong.

Into which of these two categories does preservation fall?

Usually, we can just wait and see. Most hypotheses are wrong, most inventions fail, most clinical trials disappoint. Scepticism is healthy.

But preservation poses a unique challenge, as it’s very premise is that it's a two-part technology:

Preservation and storage: relatively straightforward, possible with existing techniques

Revival: extremely challenging, likely decades away at minimum

Here's the challenge: if revival becomes possible in 2125, but would have worked on bodies preserved since 2025, we'll have lost a century of lives that could have been saved. This puts us in an uncomfortable position. We can't just wait for proof - we need to evaluate preservation's potential based on theoretical arguments and current evidence.

Performing that analysis, and evaluating the potential of any proposed preservation protocol, isn’t simple. At the lowest level, it requires knowing the technical details of how preservation supposedly stabilises the microscopic biological features that store someone’s memories, personalities, desires, and other psychological traits. At the highest level, it requires understanding how the procedure would fit into the philosophical frameworks through which we understand life, death, and personal identity. Only then could we judge whether preservation might actually work.

That's why I spent four years investigating this question. After all, I was at least somewhat qualified to look into it. As a neuroscientist, I'd spent my PhD studying how genes and environments shape our cognition, and my postdoc years wrestling with the thorny problem of consciousness. If I was one of the few neuroscientists willing to take preservation seriously enough to really examine it, at least I didn't have to worry about the competition publishing first.

So, starting in late 2020, I went to work3. I dug deep into the literature on preservation protocols. I researched what happens in dying brains, from the moment blood flow stops until cells disintegrate. I examined theories of personal identity, studied how memories form and persist, and wrestled with the ethics of life extension. The result became my book, The Future Loves You: How and Why We Should Abolish Death, published late 2024.4

In the end, I think the preservation advocates are right. Current methods like aldehyde-stabilized cryopreservation have a reasonable chance of working. If I were dying, I would choose preservation. If someone I loved were dying, I would want them to seriously consider it.

Of course, we won't know for certain until the first successful revival (or until science proves it impossible). But I believe the case is strong enough that we should be offering preservation now to anyone who wants it now.

Yes, maybe one day we'll have anti-aging therapies. But the 150,000 people who will die tomorrow, and the next day, and the day after that, can't wait. For the foreseeable future, if they want a chance at a longer life, preservation is the only credible option.

Promoting preservation

Unfortunately, in the seven years since the Brain Preservation Foundation's prize was awarded, the medical and scientific communities haven't embraced this technology. There are no preservation specialists in hospitals, no professors teaching it in medical schools. Most people only know it from science fiction.

It's not that experts have found fatal flaws in the premise or proven it can't work. They're simply ignoring it until someone demonstrates revival - a chicken-and-egg problem that could cost millions of lives.

That is why I worked so hard to get my book published. That’s why I’ve been doing interview after interview during and after the book tour that followed. That’s why I’ve tried to find out what the neuroscience community thinks the probability is that aldehyde-stabilized cryopreservation could preserve a person’s memories (turns out, they give it a ~40% chance of working - more details in a later post).

And that's why I’ve started this newsletter. I want to investigate, document, and promote efforts to make preservation universally accessible. I want to track new developments in the field and share them with you.

Sure, this may all be in vain. Maybe. Future scientists might prove that 2020s preservation techniques didn't work. Sadly more probable is that preservation works, but - due to nuclear war, devastating pandemics, runaway climate change or rogue artificial intelligences - our civilization is destroyed before we ever have a chance to make revivals happen. If we don’t develop the right preservation infrastructure today, or if we fail to provide a prosperous and safe future for the people of tomorrow, then all of this will come to naught.

Yet nothing in life is certain, not even death. Just as our ancestors couldn't have imagined a world where half of all children didn't die before fifteen, where simple infections weren't death sentences, where famines were rare instead of routine, perhaps we're standing at the edge of another revolution in human flourishing.

Maybe preservation will work. Maybe you could gain control over your life and health. Maybe you’ll get to choose how long you’ll live for, and under what circumstances. The key word here is choice - rather than having the length and flow of your life ultimately determined by fate, you would have the freedom to decide your own path. You might still choose to conclude your journey someday, but it would be on your own terms, guided by your own values and desires rather than biological inevitability.

This goal is admittedly aspirational. We won't save everyone. Too many are dying today, before preservation is widely available. Too many still live in poverty, lacking access to adequate healthcare. Too many stories are ending before their time.

But every medical breakthrough started with someone refusing to accept death and disease as inevitable. The researchers who developed vaccines, the engineers who built sanitation systems, the farmers who created high-yield crops - they all helped build a world where their children could live longer, healthier lives than they did. They made you one of the lucky ones.

Now it's our turn. Just as our ancestors' efforts enabled us to exist to read these words, perhaps our modern efforts could let future generations choose how long and in what manner they will live their lives. And maybe, if we work hard enough to give them a prosperous, peaceful world, they'll choose to bring us along to share it with them.

This newsletter will document both my own and others’ efforts toward this goal. I hope you'll join me on the journey.

If you’re interested in an introduction to the field, I’d recommend Ageless by Andrew Steele as a particularly good.

Note that Bedford was not actually the first attempted preservation though. That occurred for some unnamed person in 1966.

The combination of COVID lockdowns and my partner studying for her medical exams led to a very studious environment. I’m not sure I’ll ever be as productive as that time again.

Excited you are starting a blog!

"The combination of COVID lockdowns and my partner studying for her medical exams led to a very studious environment. I’m not sure I’ll ever be as productive as that time again." For a couple of months there, the initial Covid era was highly productive for me as well. For me there was also a component of "well there's next to nothing I can do about Covid, but perhaps brain preservation research will still be useful for me and others one day."

Excellent essay, Ariel. In my own book-in-progress, I recently finished writing about the factors behind acceptance of death. I'll have to go back and add the reference you provided showing that 70% of people suffering pain and close to dying STILL want to live longer. The gap between philosophical statements favoring death and actual behavior when confronting death is vast.